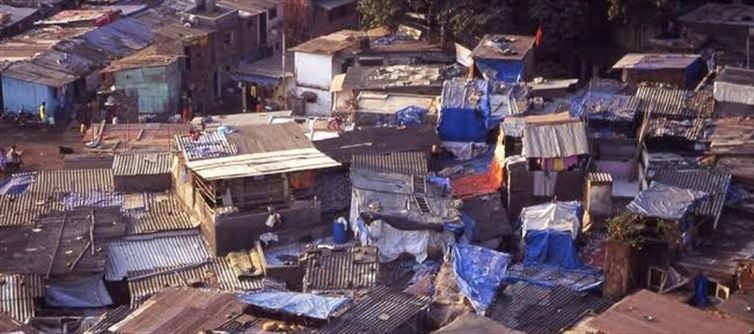

A R Antulay, the then chief minister of maharashtra, declared in 1981 that he would clear out all of Bombay's slums since most of them had overgrown the pavements and left little room for people to walk. Most films from the 1970s and 1980s depict a builder clearing land with bulldozers or thugs to eradicate a slum. What transpired in bombay in 1981 is the source of that subject.

Antulay said that the state is powerless to better the living circumstances in these slums and that residents lead the worst life possible. Social and health risks. Elevated rates of crime, women's privacy, and the need to eradicate the slums were the main points of contention.

The BMC of mumbai Municipality began the eviction process. They used a provision of the BMC Act, 1888, which said that "trespassers" on government land might be removed without giving previous notice.

In mumbai, protests got underway. Two slum organizations petitioned the bombay High court, arguing that since they had lived in the slums for such a long time, it was their right to do so.

Olga Tellis, a journalist, also submitted a petition on behalf of those who live on the pavement. This designation would go down in history as a landmark decision, case law, and something that will save millions of indian slum residents from forcible evictions.

Why was her petition unique?

Olga Tellis filed a Second Generation Rights appeal.

Second Generation Rights are essential liberties included in the original rights but not expressly stated in the Constitution.

For example: It is crucial to your right to life that you marry the person you want. You have the right to do so. However, the Right to Choose Your Own marriage is not expressly stated.

The right to privacy is a component of the right to life but is not expressly stated in it.

Therefore, slum inhabitants did not assert that the land was theirs in Olga Tellis' suit. Rather, they asserted that they are not intruders. Because of poor living conditions, they are compelled to live in slums and on sidewalks, and they must reside near to their place of employment. According to the petition, it is a component of their article 21 Right to Life. They are unable to live far from their source of income.

The supreme court heard the matter.

The supreme court heard the matter.However, the maharashtra government and BMC made concerns about the city's social safety and health. rates of crime and encroachment on public land.

The supreme court ruled in 1985 that slum residents' Second Generation Rights were recognized. The court acknowledged that being close to a place of employment is crucial for slum residents. Their right to life will be violated otherwise.

-The sc further directed BMC to hold off on evicting anyone till after the monsoon season has ended, which is one month.

-The supreme court ruled in the 1888 BMC Act that a law need not be enforced universally merely because it exists. There must be a catch. This was said regarding BMC's right to evict without giving prior notice.

-But the court made no mention of the "right to rehabilitation" or the "right to housing." These rights belong to the third generation. It implied that those facing eviction would need to be given housing by the state under duress. No such decision was made.

Thus, "Olga Tellis vs. bombay Municipal Corporation, 1985" rose to prominence as one of India's most significant landmark rulings.

We observe how illegal communities receive water and power connections, water tankers are sent to them, restrooms are constructed for them, immunizations, education, and other amenities.

All of that resulted from the Olga Tellis case because people have the right to life and other related rights even in unofficial settlements.

Currently, evictions also need prior notice. It also includes a section about monsoon months.

This is how Mumbai's Dharavi and other large slums were spared. This is how the sequences from "basti jala do" in bollywood films were dropped since they were no longer relevant.

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel