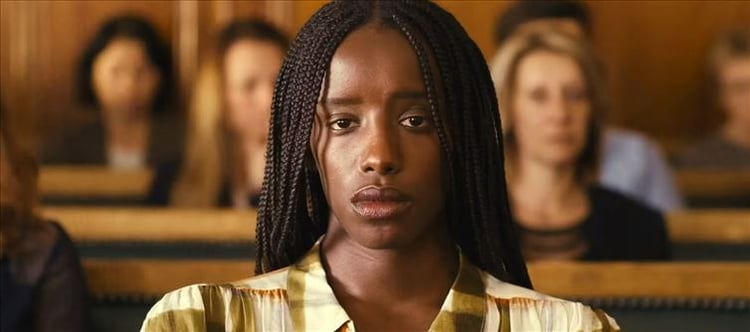

A professor and author of Senegalese descent named Rama (Kayije Kagame) makes the trip from paris to the commune of Saint-Omer for the infanticide trial of one Laurence Coly (Guslagie Malanga). The nation is intrigued by this case because of its unique features—Laurence, who has confessed, enters a plea of not guilty after asserting that he was under the spell of witchcraft. Rama plans to compare it to the mythological story of Medea and use it as the foundation for a new book. Laurence's story, though, makes her realise how many aspects of her own life are similar. The accused, a Senegalese immigrant, moved to france to pursue academic studies. Courtroom dramas can be deceptively difficult to direct because there isn't much movement in the environment naturally, but Diop's formal assurance embraces the static without being stuffy. As Laurence and other witnesses are questioned by the judge (Valérie Dréville), the prosecuting attorney (Robert Cantarella), and the defence attorney, Vaudenay (Aurélia Petit), the camera is typically locked in specific positions. Except for a few infusions of Rama's perspective, these sequences play out like recreations of genuine transcripts (those of the true case did in fact serve as the inspiration for the screenplay), but the filmmaker is not only drawing on her experience as a documentarian. Saint Omer derives significance from deliberate, unostentatious decisions.

Courtroom dramas can be deceptively difficult to direct because there isn't much movement in the environment naturally, but Diop's formal assurance embraces the static without being stuffy. As Laurence and other witnesses are questioned by the judge (Valérie Dréville), the prosecuting attorney (Robert Cantarella), and the defence attorney, Vaudenay (Aurélia Petit), the camera is typically locked in specific positions. Except for a few infusions of Rama's perspective, these sequences play out like recreations of genuine transcripts (those of the true case did in fact serve as the inspiration for the screenplay), but the filmmaker is not only drawing on her experience as a documentarian. Saint Omer derives significance from deliberate, unostentatious decisions. It also demands a lot of the actors, who receive a certain amount of thematic precedence as a result of this editing approach. Consider the time that Charlotte Clamens, Laurence's former philosophy professor, questioned the legitimacy of her interest in Wittgenstein because of his distancing himself from her African culture. The camera first catches Laurence's reaction, which threatens her resolute demeanour as his enraged gaze transforms into something resembling insecurity and defeat. When the judge informs her that she must remain standing when she sits, she immediately looks dejected. The protagonist then casts a contemptuous stare as the professor re-sits down next to Rama, her own rage seething beneath a body language that is unwavering.

It also demands a lot of the actors, who receive a certain amount of thematic precedence as a result of this editing approach. Consider the time that Charlotte Clamens, Laurence's former philosophy professor, questioned the legitimacy of her interest in Wittgenstein because of his distancing himself from her African culture. The camera first catches Laurence's reaction, which threatens her resolute demeanour as his enraged gaze transforms into something resembling insecurity and defeat. When the judge informs her that she must remain standing when she sits, she immediately looks dejected. The protagonist then casts a contemptuous stare as the professor re-sits down next to Rama, her own rage seething beneath a body language that is unwavering.

Although there are certain formal flourishes in Diop's film, especially when it comes to probing Rama's early recollections, the focus is on gathering significant facts rather than establishing overarching, definitive claims. Saint Omer benefits from research as befits its interest in academia, and viewers will find that reflecting on it later reveals fresh links. For instance: Is Rama actually drawn to Laurence to the extent that she is compelled to picture herself in that improbable situation? Or perhaps she recognises elements of Laurence in her Senegalese mother and wonders how close she was to meeting the same end as the child.

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel