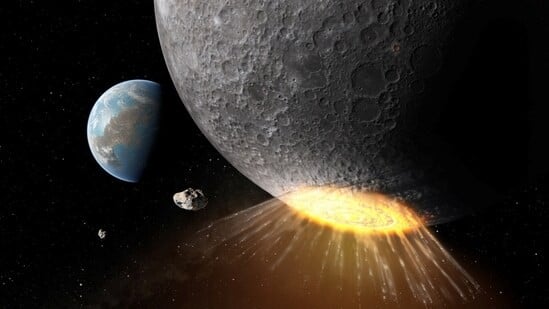

Asteroid collision carved 2 massive 'grand canyons' on the moon in 10 minutes

A new study by US and british scientists has revealed that an ancient asteroid collision near the moon's south pole created two massive canyons, each the size of the Grand Canyon in Arizona, in just 10 minutes, according to findings published in the journal Nature Communications on Tuesday.

This discovery is seen as positive news for scientists and NASA, who are planning to land astronauts on the untouched, Earth-facing side of the moon's south pole, which is believed to contain older rocks in their original condition.

The researchers mapped the area using data and images from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and tracked the debris path that formed the canyons. The study suggests that the canyons, located in the "Schrödinger impact basin" on the moon's far side, were carved in less than 10 minutes by debris launched into the air when an asteroid or comet impacted the lunar surface around 3.8 billion years ago.

This collision released around "130 times the energy of the current global stockpile of nuclear weapons," according to geologist David Kring of the Lunar and Planetary Institute, university Space Research Association in Houston, and lead author of the study.

How the canyons were discovered: All about the study

Scientists used data from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and computer modeling to track the speed and direction of debris from the asteroid impact. They found that the debris traveled at speeds of up to 2,200 miles (3,600 km) per hour.

"Vallis Planck, one of the canyons, is about 174 miles (280 km) long and 2.2 miles (3.5 km) deep. "Vallis Schrödinger, the other canyon, is roughly 168 miles (270 km) long and 1.7 miles (2.7 km) deep.

The space rock that struck the moon passed over the south pole, creating a large basin and sending boulders speeding at nearly 1 mile per second (1 km per second). The debris carved out two canyons in under 10 minutes, which is much faster than the millions of years it took for the Grand Canyon to form.

This impact occurred during a period of heavy bombardment in the inner solar system, during which space rocks were likely dislodged due to changes in the orbits of the solar system's giant planets.

The object that struck the moon is estimated to have been 15 miles (25 km) in diameter, more significant than the asteroid that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

Geologist David Kring explained in the journal that because debris from the Schrödinger impact was thrown from the lunar south pole, ancient rocks in that area will be close to the surface, making it easier for Artemis astronauts to collect them. These samples will offer insights into the moon's early history.

These rocks will help test the theory that the moon formed after a large impactor collided with Earth, sending molten material into space. They will also shed light on the hypothesis that the moon's early surface was once a vast ocean of magma, Kring added.

Kring also said that it is unclear whether these two canyons are permanently shadowed, similar to some of the craters at the moon's south pole. "That is something that we're clearly going to be reexamining," he said.

Permanently shadowed areas on the moon's surface are thought to contain significant ice, which could potentially be used to create rocket fuel and drinking water for future moon explorers.

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel